In this blog post I will explore the ways in which Market thinking, where the ‘Market’ is defined as the system of exchange and valuation of goods[1], permeates beyond its detached scope. I make the argument that we have, subliminally, allowed an objective concept to subjectively influence our collective narratives, including: what is important, how we should feel, who should benefit, and progress more broadly. In this article I support my argument by examining the problematic symptoms of this pervasive and invisible force through time, culminating in the present day. Our story starts during the English Industrial Revolution in 1811, the East Midlands.

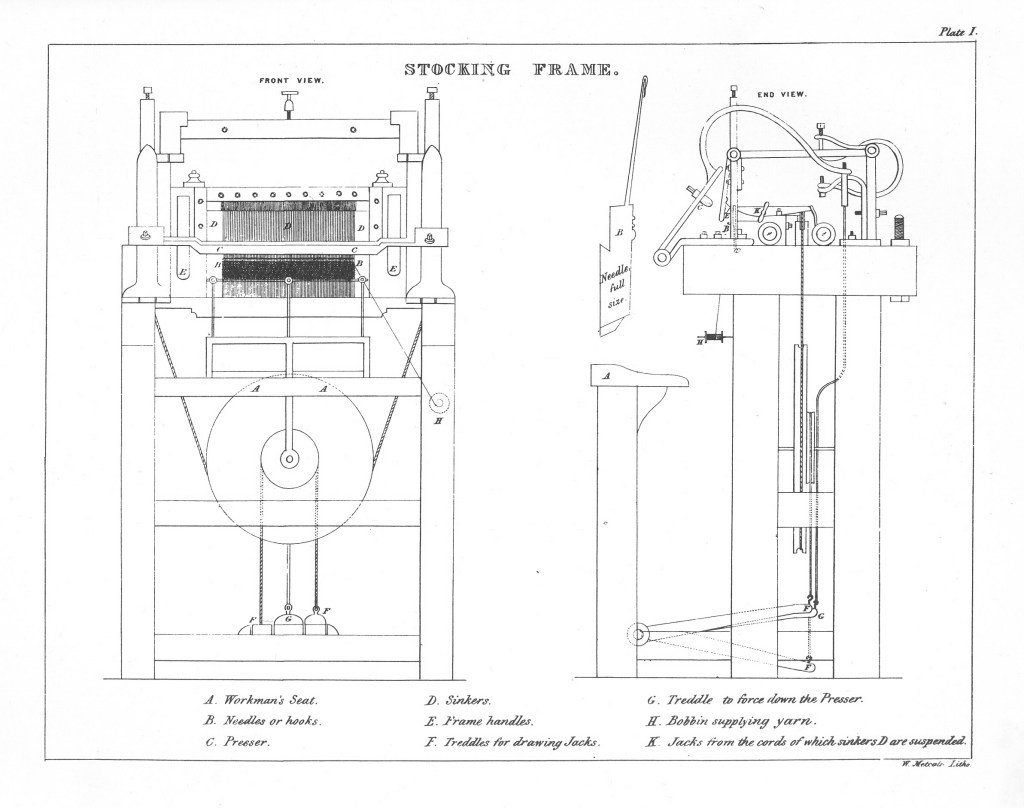

A committee of Silk Stocking Makers, known as Framework-knitters, gathered at the Fox and Owl Inn, Derby, on the 9th of December. In nearby Nottingham, Wide Frames, machines allowing wider fabric cut-ups to be made more cheaply and efficiently at the cost of finishing quality, had been introduced [2][3]. The craft of Frame Knitting, using materials like silk, lace, and cotton to produce Hosiery was a significant industry in the East Midlands by the 19th century, and, like elsewhere, many artisans saw these machines as a threat to their livelihoods[4] as well as the quality of their craft[3]. We have an idea of the sentiment felt at the Fox and Owl by the publication made in the Nottingham Review on the 20th December 1811. One sentence was particularly poignant:

“We are at a loss to know where to fix the stigma (too much blame being due to ourselves for not watching better over the trade) as each striving to manufacture on the lowest terms, makes us little better than mere engines to support a jealous competition in the market.” – Derby Committee of Plain Silk Hands [5]

There is an implication that these Silk Hands have been the subject of criticism or, at least, lack of compassion regarding their circumstances i.e ‘Stigma’. Clearly, they had a keen perception of the wider Market forces of which they were not the benefactors: ‘mere engines to support a jealous competition in the market.’ Should they really feel shame for not showing better due diligence? Why are the victims of unemployment, which meant destitution in 1811[4], being tarred by the authorities as the “depredators”[5]? Surely, their economic problems are simply economic problems – and no deeper. Some readers may already know that this rhetoric by the working class, and the subsequent riots to break the machines attributed to their wage-deflation[6] were carried out by the Luddites. A term which has been quietly perverted to refer to a technophobe, backward-thinker, or someone with a penchant for pointless menial work. The fact that machine-breaking became punishable by death in 1812[6] suggests that the authorities of the time would have supported such connotations of a ‘Luddite’. I think it would be an oversimplification to say this extreme reaction by authorities was simply and solely due to power-threatened sadism. As Cartwright’s historical account puts it, in the Industrial Revolution, there were strong profit incentives for labour cost cutting innovation, and favourable conditions given by governments to Capitalists to invest in those inventions[7]. The Luddites were certainly going against the grain, so to speak. The Market forces are at work: high supply means cheaper goods for the consumer, more profit for private owners, necessitated by cheaper labour market value. The bottom line is forfeit. This is a cold equation, however, the Market conditions did not brand the struggles of the Luddites. Nothing about this new Market System (Capital ‘S’) in isolation is subjective, yet the moral questions it raised regarding the workers’ Market de-valuation were viewed dismissively. Without a pause for thought in the present day, ‘Luddite’ is still seen as a byword for hindrance to progress.

Fast forward nineteen years to 1830 in the agricultural south of England and another machine-breaking movement was boiling over. A bad harvest and the bitter winter of 1829 had set the scene for rioting in the following summer in East Kent. Again, typified by the targeted destruction of machinery[8]. There are, as I would conjecture true in the case of the Luddites, complex and debated causal factors behind the ‘Swing’ Riots, named after their leader/phantom ‘Captain Swing’[8][9][10]. The broad sweeping Enclosure Laws, as one example, offers a fascinating insight into the nature of the controversial changes and how those changes could be perceived to be Market goal-posted and optimised. The state that had existed in the Middle Ages was the Manorial Open-field system. In this traditional system tenants (Serfs) had the rights to cultivate a subdivision of the land owned by a manor lord[11][12]. Other areas of this land, called ‘commons’, supported the local community by right of access to pasturing, livestock, fishing and personal use[13]. The manorial court, made of ‘Commoners’, required a degree of coordination to synchronise the harvests, grazing and had consensus voting on general decisions regarding its use e.g irrigation between the many shared plots and tenants[14]. The enclosing of the land which had originally been informal was now supported by an Act of parliament during the 18th century and had become the norm by 1750[15]. This was ultimately a step of privatisation on the part of the landlord and revoked the tenant’s traditional right to farm their plot in exchange for protection and, subsequently, access to the commons. The patchwork of tenanted land, on the other hand, prevented the ‘economy of scale’ and agricultural innovation had been slower due to group decision making[14]. The enclosing of this land had the effect of increasing yields, profits or, at least rents, for the landowners [15][13][16], but creating the landless poor who became solely dependent on work privately offered by the land owner to survive[10]. At this point, it seems like we have observed the harsh collateral damage of Market’s max-sum game. Progress, to my mind, has manifested again as a polarising choice between social and private issues with the Market’s insatiable desire for more goods and reduced labour costs seemingly providential. Like the Luddites, Griffin argues that this is tantamount to “internal colonisation” along with the perception of the poor as a Subaltern, paving the way for a manifesto of global colonialism[17].

Was there not truly a third, more humane way, to incentivise growth without the expense of creating landless poor? I wonder if the Enclosure Laws could have instead been the beginnings of a more formal land cooperative. Traditional plots could have been consolidated irrespective of geographical ownership and the profits of machine working could have been shared on enclosed (but still co-tenanted) land, providing, crucially, it still was actually worked by the cooperative members. Caprettini and Voth, make a seductive but tentative causal link between inverse likelihood of a Swing-esk riot and proximity to industrial centres, which would have provided another but probably quite onerous employment for those who had now lost agricultural work and subsistence through the commons[18]. These decisions, who should work where, who should benefit, seem like both the force and the course of a ‘natural’ progression. But, of course, our acceptance of this reality as a matter of fact shows how deeply we take it for granted. Assuming the premise that a supply-demand influenced barter system manifests regardless of what we think, the real question is why society’s ‘optimal’ configuration of growth wins out versus the needs of the Luddites and Captain Swing.

We have seen very tangible implications of Market prioritisation but this assumption of the ‘Market right of way’ on thinking can be more broadly discussed. The book or, more accurately, the slightly abstract hook of Bauman’s title ‘Liquid Love’ inspired this post. Although I disagree with many of his inferences, Bauman’s perspective is an interesting observation about attitudes and realities of the dating scene at the time of writing. Quoting columnists, the impression he gives is that consumerist thinking had emerged in the dating scene, leading to overly individualistic fanciful habits with “long-term commitments thin on the ground”[19]. I find this sentiment quite unfair to the individual. Presumably, the relative abundance of choice of partners enabled by social situations would have been a stark contrast to life as Bauman knew it as a young adult[20]. However, the supporting consumerist metaphors he used to unpin his points speak profoundly towards the Market Monopoly on thought. For example, he compares the opportunity of interaction to that of a shopping mall, “shopping malls tend to be designed with the fast arousal and quick extinction of wishes in the mind”[19]. There is a pivot here, however. A shopping mall or a marketed product of any kind is a heavily curated experience – not necessarily one we would gravitate towards of our own volition. And, although I agree that our participation in the Market is effectively involuntary, I think most people are actually aware of this; like the Luddites were. The real risk is to sleepwalk into negative side-effects of permissive consumerism, or assume others will, or should, as a result of passivity.

But why does this all matter and what relevance does it have to today? Anthony Giddens, is another contemporary Sociologist who contextualises our question well. He frequently references the term ‘Reflexivity’. Reflexivity represents internal interrogatives to our experiences and actions to better understand individual behaviour and motivations[21]. Giddens describes our ‘living’ biography reflexively ‘organised in terms of flows of social and psychological information about possible ways of life’. Influenced, in his example, by self-help writings he argues that such discourse is constitutive of our collective, then pervasively internalised, knowledge about possible ways of life[22]. This provides the formal framework to carry our point in this post. Our internal narrative for the ways in which we reach ‘achievement’ comes from a palette influenced by motivational speakers, Linkedin (more on this later), fantasy advertised realities, and the platform supplied to financially successful business leaders and their backers. Our self-reflection becomes pigeon-holed by these perspectives, made manifest by their personal proximity to a favourable Market position, both dying and limiting the spectrum of our own answers to the reflexive ‘how’. In other words, our future biography to achieving self-actualisation becomes informed and providenced by our interaction with a Market, and (economic) success becomes contributive, but also broadly transgressive of other possibilities to reflexive answers. Gideons writes: “Holding out the possibility of emancipation, modern institutions at the same time create mechanisms of suppression, rather than actualisation, of self”[22]. This ultimately means that our route to self-actualisation is necessitated only by our capacity to exchange goods. That is, if we are so lucky to sit at the peak of Maslov’s Hierarchy of needs to begin with; unlike the Luddites and, tragically, many alive today. Although many involved with the exchange of goods provide an incredibly valuable contribution, arguably a society totally enraptured and organised around this concept should not be blindly conflated with overall good. This orientation provides the course in the education system too, noted by Säfström and Månsson on the increasing Markestisation of Swedish schooling. They argue that neo-liberal policy re-organises teaching around learning outcomes which are valued in terms of the imparted competitive edge – leading to education merely for earning and not “making a life”[23]. Right out of the gate, so to speak, our stars become aligned such that it is seemingly only possible to compete for them adversarially, when we can reach them (literally) together. In this adversarial system the risk is not only the means to personal fulfillment but also the loss of empathetic global citizens.

The last stop on our journey brings us to the omnipresent dialogue on “AI”, perhaps the “Wide-frames” industrial mechanisation of our time. These two letters alone are sure to make some readers’ eyes roll and this feeling of exasperation is worth exploring. In fact, the questions regarding why the AI dialogue is so omnipresent and so relentless, can be partially explained by the Market Monopoly on thought. It feels like the prevailing line on “AI” is always: “get on board, or get left behind”. A demonstrative example of this line has been provided by Linkedin’s own blog. This blog gives Linkedin’s impression of ‘Talent Trend’ through data gathered from the platform. To support associative claims that using AI may make employees “5x more likely”[24] to develop skills such as emotional intelligence they provide the following explanation:

“Employees skilled at using GAI (Generative AI) are measured by members who have added at least one GAI skill, such as ChatGPT, to their LinkedIn profiles. Overall promotion rate is measured using the median ratio of total promotions by total average headcount, and leadership promotion rate is measured using the median ratio of total managerial level promotions by total average headcount, both in the last 12 months. Only full-time employees are considered in companies with more than 100 employees.

The likelihood of developing a soft skill is determined by dividing the proportion of GAI skilled members who upskilled by the proportion of non-GAI skilled members who upskilled a given soft skill in the last 12 months.” – Linkedin Talent Trends [24]

Not only does AI get you promoted, it makes you more personable too! Clearly, there are very dubious correlation-causation conclusions attributing AI as a causal factor to promotions (for what that is worth), as documented by Linkedin profiles. Naturally, we can be skeptical of our source anyway. Greater engagement with Linkedin is probably the goal of this post which is nicely demonstrated by users adding skills to their profile. Further, those that do engage in Linkedin are probably aware of the performative advertisement of adding skills to their profiles – whether or not these are actually verifiable. It is hardly surprising that we believe that AI is being carried on the wind by natural forces when even authors in the technical development of AI remark at the market hedging its bets on “Agentic AI” [25]. As a result, the narrative that nets jobs (the gateway to Maslov’s upper and lower echelons) is almost hysterically compelling us to do no other for the sake of our careers. Who constructed such an empty truism? Like the Wide-frames in Luddite times, my belief is that AI as a tool can simply reduce the ‘bottom-line’ through efficiency gains leading to more profit and more growth. Like the Wide-frames, expensive and inconvenient skilled workers can now be causally moved aside. Like the Wide-frames, there is no mention of how this concretely benefits democratic society at large, or what that society will look like. Unlike the Wide-frames, we are already enchanted.

But how do we even begin to address this monolithic and deeply foundational issue? If you are reading this: good. A label already forms in our collective conscience. Even emotional or experiential awareness often lacks a discursive label to constitute the premise for further thought, let alone action. Awareness is the first step. The next step, in my opinion, is hope. We live in a time where simple, often contradictory binary labels, are seductive as they are divisive. But, the reality is this: your idealism does not have to come at the expense of your pragmatism. How could Universal Suffrage or any human-centric movement be conceived in the first place without a dash of idealism? We are barraged daily with outrage bait through click-driven journalism such that it takes a leap of faith to believe that ‘it is what it is’ is not all humans are capable of. But, this artificial reality is a curation of the Market Monopoly on Thought too. Forearmed with hope, we can take steps towards a more humane system which applies globally. A system where societies are not directly or implicitly pitted as adversaries, and individuals are held accountable. Where the foundation of thought is that people are ultimately good and needn’t be forcibly organised into a hierarchy for life or a “World Order”. The problem with the Market Monopoly of Thought is that all of our outcomes are bonded by capital and the exchange of goods. Where growth for growth’s sake has carelessly displaced the Luddites and found a way to meticulously de-empathise our struggles, reorienting society to push wealth upwards like it did before with the Enclosure Acts. The Market Monopoly of thought means that the direction and nature of human effort is controlled through capital and not humanity. We yet again, approach the perilous shores of mechanisation. Will we use these tools to benefit us all or will we be cowed by the Market narrative?

You may have wondered why this post has not focussed on greed or individual faults, but solely a systemic problem. To answer that I leave this quote:

“An uninstructed person will lay the fault of his own bad condition upon others. Someone just starting instruction will lay the fault on himself. Some who is perfectly instructed will place blame neither on others nor on himself..”

– Epictetus, The Enchiridion

References

[1] Kenton, Will (2025). Market: What It Means in Economics, Types, and Common Features. Intestopeia. Available at: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/market.asp, (Accessed 09/08/2025)

[2] Becket, John. (2012). The Luddites. Nottingham Heritage Gateway. Available at: http://www.nottsheritagegateway.org.uk/people/luddites.htm

[3] (2025). Frame Knitting. Heritage Crafts. https://www.heritagecrafts.org.uk/craft/frame-knitting/, (Accessed 09/08/2025)

[4] King, David. (2011). The Luddite uprisings – lessons for technologypolitics now. SGR News Letter, Issue 40. Available at: https://www.sgr.org.uk/sites/default/files/SGRNL40_luddites.pdf (Accessed 11/08/2025)

[5] Binfield, Kevin (2015) Writings of the Luddites. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 81

[6] (2025). Why did the Luddites Protest. The National Archives. Available at:https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/why-did-the-luddites-protest/ (Accessed 09/08/2025)

[7] Cartwright, M. (2023, May 02). British Industrial Revolution. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/British_Industrial_Revolution/ Cartwright (accessed 09/08/2025)

[8] Knight, David (2019). The History of the Swing Riots in Berkshire. Penny Post. Available at: https://pennypost.org.uk/2019/03/the-history-of-the-swing-riots-in-berkshire/ (accessed 09/08/2025)

[9] Aidt, T. S. (2017). “The Social Dynamics of Collective Action: Evidence from the Captain Swing Riots, 1830-31,” RePEc: Research Papers in Economics. RePEc: Research Papers in Economics. doi: 10.17863/CAM.15514.

[10] HLB. (2020). The Swing Riots. Hampshire History, available at: https://www.hampshire-history.com/the-swing-riots/ (accessed 09/08/2025)

[11] Morten, Thomas (2023). The Enclosure Act’s Impact on British Landscapes Available at: https://ruralhistoria.com/2023/05/24/enclosure-act/ (accessed 09/08/2025)

[12] ‘Manorialism’ (n.d.) Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: Britannica (Accessed: 11 August 2025)

[13] Davidson, Jessica (2025). What are commons? Available at: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/discover/nature/what-are-commons (accessed 09/08/2025)

[14] Harris, C. McKenna, C. (2022). Enclosing the English Commons: Property, Productivity and the Making of Modern Capitalism. Oxford Centre for Global History. pp 2-3. Available at: :https://globalcapitalism.history.ox.ac.uk/files/case26-enclosingtheenglishcommonspdf (accessed 09/08/2025)

[15] (2025). Enclosing the land – UK Parliament . Available at: https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/towncountry/landscape/overview/enclosingland/ (accessed 09/08/2025)

[16] Kain, Roger J. P.. Chapman, John and Oliver, Richard R. (2004) The Enclosure Maps of England and Wales, pp. 1595-1918, available at:vhttps://assets.cambridge.org/97805218/27713/excerpt/9780521827713_excerpt.pdf

[17] Griffin, C.J. (2023) ‘Enclosure as Internal Colonisation: The Subaltern Commoner, Terra Nullius and the Settling of England’s “Wastes”’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 1, pp. 95–120. doi:10.1017/S0080440123000014.

[18] Caprettini, Bruno, and Hans-Joachim Voth. (2020). “Rage against the Machines: Labor-Saving Technology and Unrest in Industrializing England.” American Economic Review: Insights 2 (3): 305–20. DOI: 10.1257/aeri.20190385

[19] Bauman Z (2003) Liquid Love: On the Frailty of Human Bonds, Cambridge: Polity. pp. 12

[20] Twilley, N. (2010). A Cocktail Party In The Street: An Interview With Alan Stillman. Available at: https://www.ediblegeography.com/a-cocktail-party-in-the-street-an-interview-with-alan-stillman/ (accessed 09/08/2025)

[21] Ide, Y., & Beddoe, L. (2023). Challenging perspectives: Reflexivity as a critical approach to qualitative social work research. Qualitative Social Work, 23(4), 725-740. https://doi.org/10.1177/14733250231173522 (Original work published 2024)

[22] Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity; Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Polity Press. Cambridge. pp. 14

[23] Säfström, C. A., & Månsson, N. (2021). The marketisation of education and the democratic deficit. European Educational Research Journal, 21(1), 124-137. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041211011293 (Original work published 2022)

[24] Oei, Tanya. (2024) Global Talent Trends. available at: https://business.linkedin.com/talent-solutions/global-talent-trends (accessed 09/08/2025)

[25] Belcak, P., Heinrich, G., Diao, S., Fu, Y., Dong, X., Muralidharan, S., Lin, Y.C. and Molchanov, P., 2025. Small Language Models are the Future of Agentic AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.02153.

You must be logged in to post a comment.